Trajectory Synthesis with Local Differential Privacy

This is the gentle introduction to our work which will be represented at VLDB 2023. Code and datasets are available at Github.

Introduction

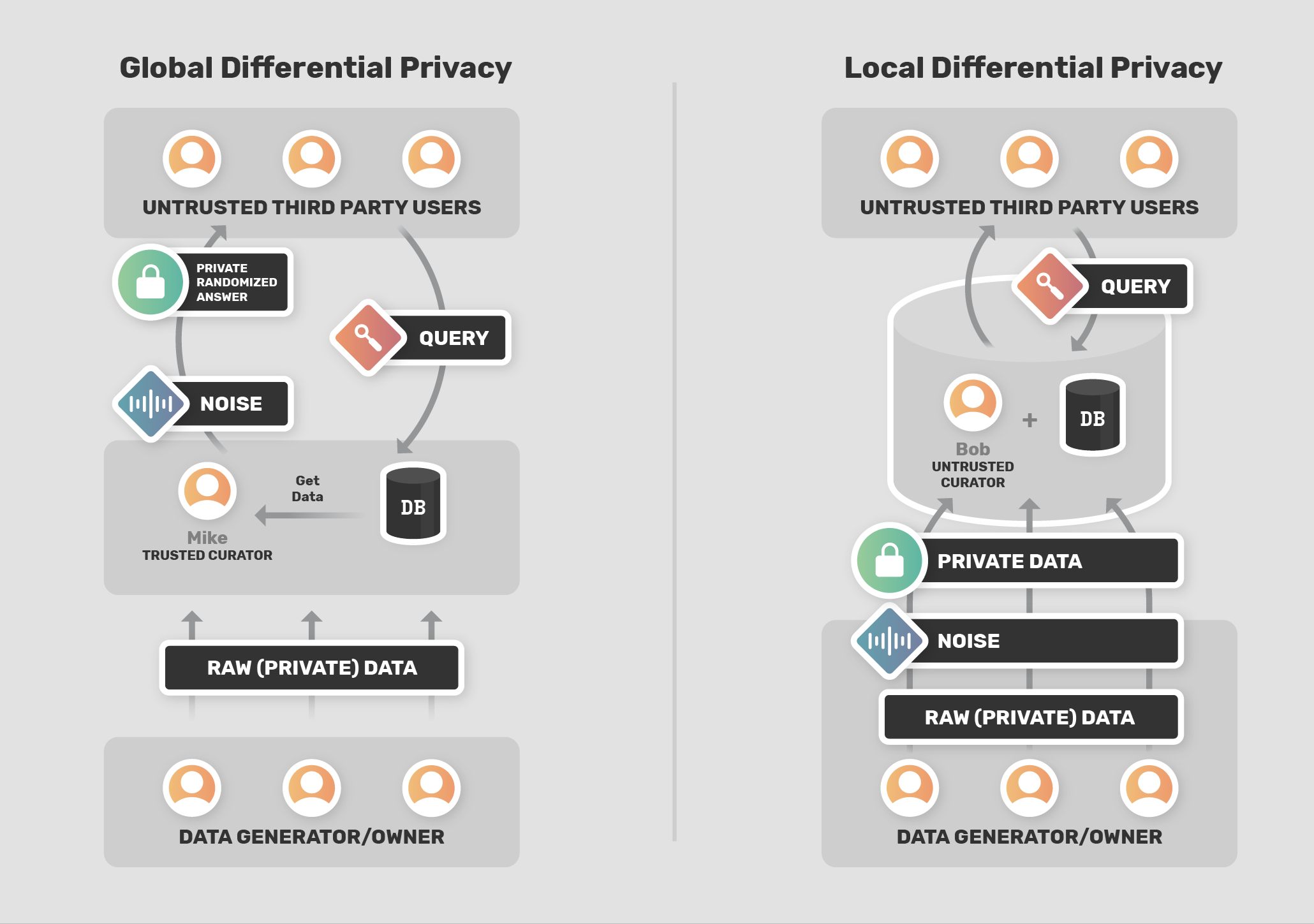

Trajectory data is widely used for many real-world applications, such as tracking the spread of the disease through people’s movement patterns and providing personalized location-based services based on travel preference. However, privacy concerns and data protection regulations have limited the extent to which this data is shared and utilized. Current differential privacy (DP) techniques rely on a trustworthy aggregator to collect users’ raw trajectories, which still suffer from the risk of data breaches from untrustworthy data curators.

In contrast, local differential privacy (LDP) allows users to directly share a noisy version of their data, provides a more practical setting and improved privacy properties. The only solution that meets the rigorous privacy requirements is NGRAM

Our approach

Overview

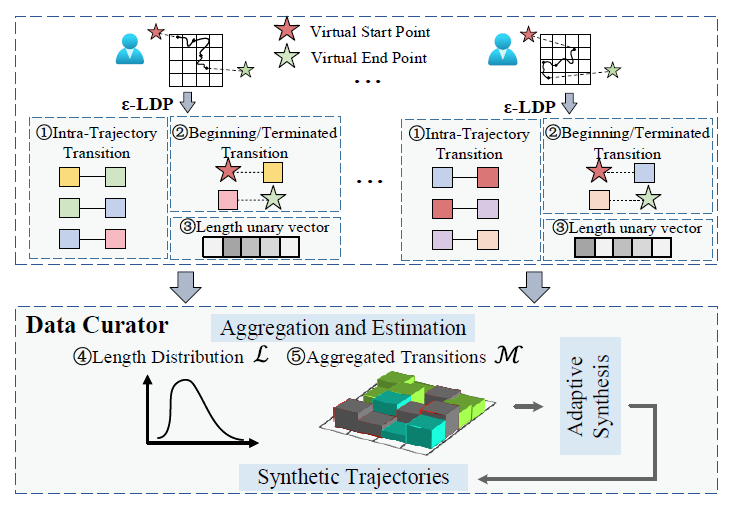

Instead of perturbing each trajectory individually, we aim to extract the key movement patterns of each user and use them to synthesize privacy-preserving and realistic trajectories. Specifically, LDPTrace approaches trajectory synthesis as a generative process, constructing a probabilistic model based on users’ transition records to estimate the global moving patterns. The key movement patterns are locally extracted from raw trajectory and perturbed/uploaded with OUE

Key movement patterns

The probabilistic model consists of three key features:

- Intra-Trajectory Mobility. Transition states are important to capture the movement of spatial data, and we model the mobility with a first-order Markov chain, which means we only care the spatial relationship between adjacent points.

\begin{equation} \operatorname{Pr}(T[l+1]=C \mid T[1] \ldots T[l])=\operatorname{Pr}(T[l+1]=C \mid T[l]) \end{equation}

-

Beginning/Terminated Transitions. Real-world trajectory usually exhibit special start point and end point, which reveal the important spatial semantic of trajectories: pickups, home/work places, destinations, etc. Besides, the start/end points are also useful to guide the random walk during synthesis. Therefore, we add two special cells, namely virtual start point and virtual end point, which are connected to all the geographic points and are perturbed and uploaded along with the mobility patterns.

-

Trajectory Length. The length distribution of trajectories is also an indispensable character of trajectory synthesis since it indicates the probabilistic travel distance of users’ trace, and serves as the deterministic constraint to terminate the synthesis process. We also use OUE to gather length information from each trajectory and form a discrete distribution on the data curator.

Trajectory synthesis

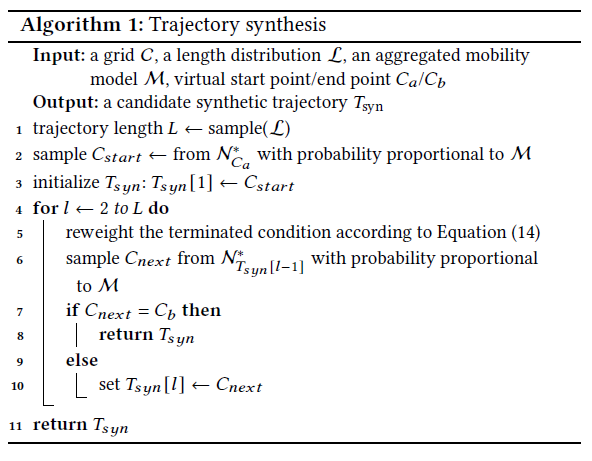

After getting the three global spatial features from trajectories, we first combine the intra-trajectory mobility with virtual start/end mobility, and utilize random walk to generate authentic trajectories from them. Here are the main steps of our synthesis algorithm:

It is worth mentioning that we found the adaptive terminated condition (line 5) is very helpful to generate faithful trajectories (otherwise it would be too short to show the spatial characters), but it is still an open question that how to integrate the handcraft adaptive mechanism into the feature selection process.

Experiments

Effectiveness

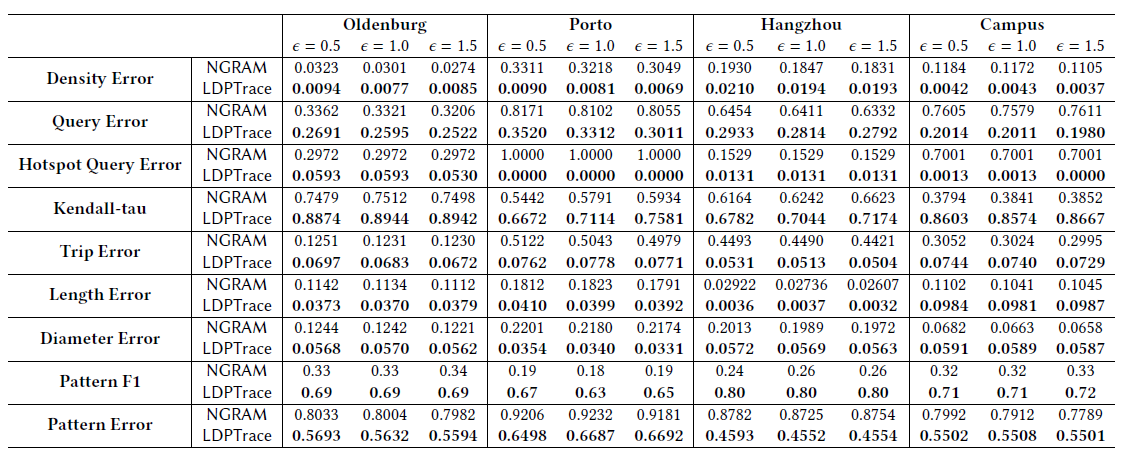

We conduct extensive experiments on four benchmark trajectory datasets (three of them are released in our repository). For utility metrics, we follow AdaTrace

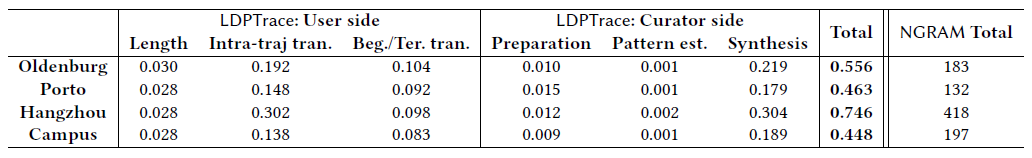

Efficiency

Efficiency is equally important as utility for real-world deployments, we conduct comprehensive experiments to evaluate the average running time of each component, as show in the following figure. We find that LDPTrace is a very efficient privacy-preserving trajectory publication framework, which is more than 300 times faster than NGRAM.

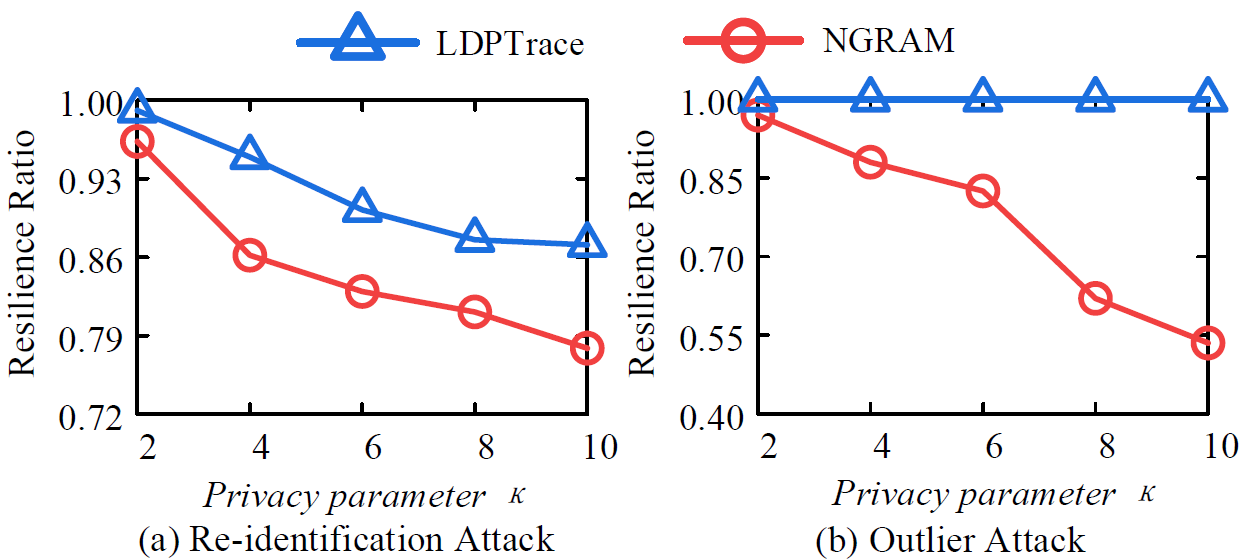

Attack resilience

We also investigate LDPTrace’s resistance to two common attacks, namely re-identification attack and outlier attack, which are defined in this paper

Ablation study

Finally, we conduct in-depth analysis with LDPTrace, like impact of beginning/terminated transitions, impact of grid granularity, impact of different query size. Please refer to our paper for details if interested.

Conclusion

In this paper, we present a neat yet effective trajectory synthesis framework under the rigorous privacy of LDP, called LDPTrace, which achieves strong utility and efficiency simultaneously. Although the privacy issues of trajectory data is extensively studied in recent year, I still think there is more room to achieve better privacy-utility-efficiency tradeoff. Maybe the synthesis approach (LDPTrace) is a plausible way.