Imitation, not Shadowing

This is the gentle introduction to our work, which will be presented at USENIX Security 2026. Code and datasets are available on Github.

Introduction

Membership Inference Attacks (MIAs) have become the standard tool for measuring data leakage in machine learning models. The goal is simple: given a data point and a trained model, determine whether that data point was used during training.

Over the last serval years, the research community has viewed shadow training

However, state-of-the-art shadow-based attacks such as LiRA

In this work, we asked a fundamental question: Is this massive computational cost of shadow training really necessary?

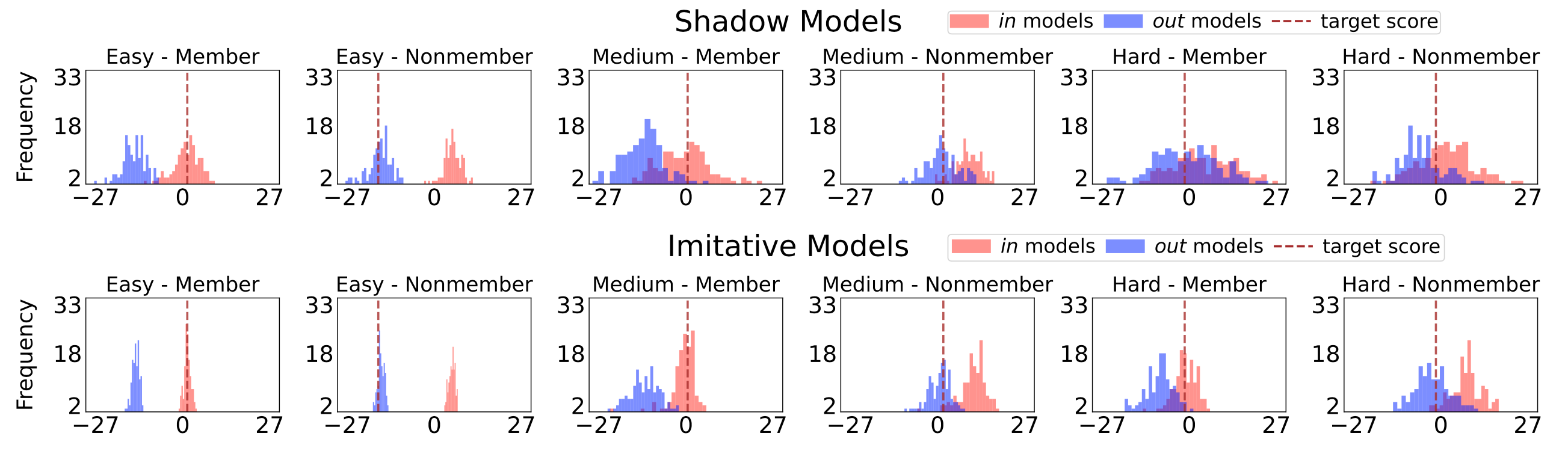

The Problem with Target-Agnostic Shadowing

We identify that much of the inefficiency in existing methods comes from their target-agnostic design. Standard shadow models are trained to learn general behavioral distributions, but they are not trained to learn the specific idiosyncrasies of the target model under attack. As a result, shadow models exhibit high predictive variance. As shown in the top row of the figure below, the score distributions for members and non-members derived from shadow models often overlap significantly, especially for “hard” instances. This variance forces attackers to train hundreds of models just to statistically average out the noise.

Our Solution: Imitative Training

To address this, we introduce the Imitative Membership Inference Attack (IMIA). Instead of training shadow models that are indepenedent from the target model, we explicitly train imitative models to mimic the target.

IMIA operates in two stages to capture the behavioral discrepancy between members and non-members:

- Imitative OUT Models: We first train a model to match the target’s output on a reference dataset. Since the target model didn’t see this reference data during its training, this imitative model learns to replicate how the target behaves on non-members.

- Imitative IN Models: We then fine-tune this model using a small set of “pivot” instances. These pivots act as proxies for members, allowing the model to capture how behavior changes when the data is included during training.

By comparing the target query’s score against these two tightly calibrated distributions (Imitative IN vs. Imitative OUT), we can perform highly accurate inference using far fewer models.

The implications of this shift from “shadowing” to “imitation” are profound.

We found that IMIA achieves superior attack performance while requiring less than 5% of the computational cost of state-of-the-art baselines.

This reduces attack time from days to hours.

This performance superiority is consistent across different attack settings (both adaptive and non-adaptive, as introduced in our previous paper

Conclusion

We believe that Imitative Training represents a paradigm shift for MIAs. By moving away from generic shadow training and towards target-informed imitation, we can assess privacy risks more accurately and with a fraction of the computation required by previous approaches.

This shift is especially important for foundation models such as large language models (LLMs). Some studies argue that current MIAs against LLMs are ineffective. However, this may not be because LLMs are resilient to privacy attacks, but simply because existing attacks are too weak or computationally expensive to run at the necessary scale. We hope our approach provides a viable solution for this direction. There are enormous opportunities to explore along this path, and we invite more researchers to join us in developing powerful, efficient privacy auditing approaches for trustworthy ML.